India Per Capita Income in Dollars

(This

is for information purposes only. This should not be construed as a

recommendation or investment advice even though the author is a CFA Charterholder. Please consult your financial

adviser before taking any investment decision. Safe to assume the author has a vested

interest in stocks / investments discussed if any.)

(All the updates, effective Jul2024, on per capita income in US dollars, are available in Indian Economy Data Bank)

According

to World Bank data for 2022, India is the fifth largest economy in the world by

gross domestic product (GDP). But in terms of per capita income, it is at

around 140th rank, indicating India is at the bottom of the pile on

a per capita basis.

Per capita income is calculated by dividing a nation's population by its total national income.

India

became world’s most populous nation this year, surpassing China. Our population is considered as our

strength. But in terms of income inequality, it can be described as our

weakness because India’s potential does not get reflected when one compares

indicators based on per capita income.

1.

India per capita income

India’s

per capita gross national income in 2022 is 2,380 US dollars. Gross national

income (GNI) is the income earned by a nation’s residents irrespective of where it is

earned. It can be calculated by adding income from foreign countries to country’s

gross domestic product (GDP).

Comparatively,

the world’s average per capita income is USD 12,804 in 2022. So, India's per capita income is less than 20 percent of world's. The

data are from World Bank’s World Development Indicators updated as on 26Oct2023.

Though

India is world’s fifth largest economy, its per capita income gets depressed

due to its population. Indian rupee’s depreciation against the US dollar also

depresses India’s per capita income expressed in US dollars.

The

official data used here is per capita GNI or gross national income. But the term

‘per capita income’ will be used here for simplicity.

Table 1: India per capita income since 2000:

As

show in table 1 above, India’s per capita income in US dollars increased from

USD 440 in 2000 to USD 2,380 in 2022, with an absolute growth of 441 percent

and an annualised growth rate of 7.98 percent – which is quite impressive in a

period of 22 years.

From

the table 1, one could observe the fastest growing years for India after 2000

are 2004, 2005, 2007, 2011, 2009 and 2006 with a year-on-year growth of 17.6,

16.7, 16.7, 12.4, 12.1 and 11.4 percent respectively.

The growth of 13.2

percent in 2021 is an anomaly because 2020 saw a severe decline of 8.7 percent in

per capita income in dollars due to draconian COVID-19 lockdowns imposed by the

Indian federal government.

(blog continues below)

------------------------------Related blogs:

Slowest growth in India's real per capita income

Why is India Falling Behind Bangladesh?

India Second Quarter GDP 30Nov2021

------------------------------

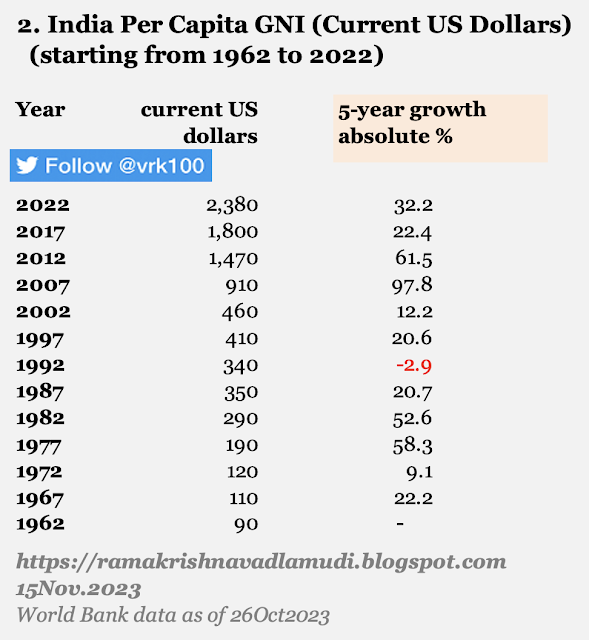

2.

India per capita income growth in five-year intervals

To

normalise for year-on-year differences, let us see how the growth occurred over

a period of five-year intervals from 1962 to 2022. The World Bank data for

India’s per capita income are available from 1962 onward.

Table

2: India per capita growth 1962 to 2022 (5-year intervals):

As

shown in Table 2, the fastest growth periods, in five-year intervals, in per capita income in dollars

are: 2002 to 2007 with an absolute growth of 97.8 percent in five years; 2007

to 2012 with an absolute growth of 61.5 percent and 1972 to 1977 with an

absolute growth of 58.3 percent.

Incidentally,

Manmohan Singh is India’s prime minister between 2004 and 2014 and Indira

Gandhi was the country’s prime minister between 1972 to 1977 (for most of the

time).

Between 1987 and 1992, India's per capita income declined by 2.9 percent due to a combination of listless economic growth and devaluation and depreciation of Indian rupee against the US dollar.

But in the past 10 years, the 5-year absolute growth rates are low compared to 2002-2012 periods. Between 2012 and 2017, India's per capita income grew by just 22.4 percent (total five years) and it improved to 32.2 percent (total five years) between 2017 and 2022.

Indian rupee devaluation:

The

numbers after 1991 are not strictly comparable with those before 1991, because

there was a regime change in 1991 not only for India’s dollar-rupee exchange rate but also

for the entire Indian economy.

Indian rupee was devalued in two stages in 1991

with a cumulative devaluation of 18 percent in US dollar terms. Dollar - rupee exchange

rate was not market-determined before 1991.

Since

01Mar1992, Reserve Bank of India, India’s central bank, introduced a dual

exchange rate system called Liberalised Exchange Rate Management System (LERMS).

It was replaced by a unified exchange rate system on 27Feb1993 to make the

exchange rate market-determined.

India's current exchange rate system is not

full float, but often dubbed as 'managed float.'

3.

Comparison with comparable countries

Most

of the things in life are relative. Let us examine how India stacks up in the

world in terms of per capita income.

Comparable

countries, like, BRICS, G20 and others are included in table 3 below to see how

India performs. As per World Bank’s 2022 data about per capita GNI of October

2023, India is a lower middle income country.

Table 3: Comparison with comparable nations:

The

World Bank categorised India as a lower middle income country. As can be seen

from table 3 above, India’s per capita income is the lowest not only among the

G20 but also among BRICS countries.

It may not advisable to compare a lower middle income nation with high income nations, but even

among lower middle income countries, India's income per head is lower than that of Bangladesh,

Egypt and Vietnam.

The per capita incomes of other BRICS nations, Brazil, Russia, China and South Africa are much higher than that of India (table 3 above).

Among upper middle income category, Malayasia, Libya, Colombia, Botswana and Iraq have per capita incomes far higher than that of India.

Countries, like, Kenya, Nigeria, Nicaragua and Burma (all lower middle income nations) have incomes lower than that of India, as per World Bank's 2022 data.

4. Summary

India may be the world's fifth largest economy but its ranking in per capita income is quite low -- even lower among comparable countries, like, Bangladesh, Egypt, Vietnam, South Africa and Russia.

In 2022, India's per capita income is USD 2,380, which is much lower than the world average of USD 12,804.

The

current narrative is crossing the USD-2,000 per capita income threshold is a

turning point for countries in the past and the same can be extrapolated to

India. India surpassed this threshold once in 2019 and again in 2021 – after having

down below the level in 2020.

The

expectation has gained ground in recent years so that India can leapfrog to USD

5 trillion. To put it mildly, this is a narrative propagated by some people to suit their interests.

When it comes to growth in per capita income and overall economic growth, the record of current Indian federal government is quite tepid, despite the hype and propaganda.

This

is not an attempt to analyse India’s prospects on a single metric like per

capita income but to put things in the perspective and throw some light on the

income disparity that has been bedeviling the country for several years.

The income inequality has worsened since the COVID-19 outbreak, with economists and experts talking of a K-shaped recovery in the country in the past three years.

Hundreds

of millions of Indians are still in poverty – this is buttressed by the fact

that the Indian federal government recently decided to extend its

free food grains programme to more than 800 million Indians by a period of five

years.

It

is fair to argue per capita GNI PPP is more relevant from India's viewpoint (we

can discuss this another time in more detail) than per capita GNI merely. GNI

PPP is GNI based on purchasing power parity, which adjusts for the purchasing

power relatively.

For

example, India’s per capita income may be low, but the purchasing power of Rs 100

is much higher in India compared to say, in the United States. To put

differently, an average meal may be available for just Rs 100 in India; the same

meal may cost more than Rs 400 or Rs 450 in the US.

It

is hoped governments in India will make sincere efforts to economically lift millions of

Indians still languishing in poverty and bring down the income equality in a

meaningful way in the next decade.

- - -

------------------------------

P.S. dated 29Nov2023: Food security:

PIB press release dated 29Nov2023: Free Foodgrains for 81.35 crore beneficiaries for five years: Cabinet Decision

Historic decision for Food and Nutrition Security : Centre to spend approximately Rs. 11.80 lakh crore in the next 5 years on food subsidy under PMGKAY

Historic decision for Food and Nutrition Security : Centre to spend approximately Rs. 11.80 lakh crore in the next 5 years on food subsidy under PMGKAY

------------------------------

References:

World Bank World Development Indicators (updated 26Oct2023)

World Bank India per capita GNI (chart available)

RBIcrisis and reforms 1991 to 2000 - chronology of events - Indian rupee devaluation in 1991 / LERMS / unified exchange rate

RBIpress release 27Feb1993 – Unified exchange rate from LERMS

PIBcircular 15Nov2023 - India providing food grains

Macrotrends India per capita GNI (graph available) (India's historical data for every year is available from 1962 to 2022; and so is data about comparable countries' per capita GNI)

Additional

Data:

India per capita GNI (in current US dollars) - starting from 1965 to 2020 in five-year intervals to compare how that data stands over five-year intervals:

G20

– Group of 20 countries

BRICS

– group of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa

------------------------------

Read more:

Blog of Blogs Theme-wise

RBI Annual Report and HBIE - Data Tables

India Foreign Exchanges Reserves Comfortable

Analysis of Small Savings Schemes and Interest Rates

Is De-Dollarization Real?

India Debuts 50-year Sovereign Bond

India: Prospects and Challenges

India Public Debt and Floating Rate Bonds

India Equity ETFs Worth Considering

JP Morgan Guide to Markets Sep2023

Mutual Fund Asset Class Returns 30Sep2023

Divergence in Volatile Global Bond Yields

India's Crude Oil Import Dependency Jumps under Modi

Buyback Offers and Weblinks

Negative Impact of Debt Mutual Fund Tax Changes

Weblinks and Investing

-------------------

Disclosure: I've vested interested in Indian stocks and other investments. It's safe to assume I've interest in the financial instruments / products discussed, if any.

Disclaimer: The analysis and opinion provided here are only for information purposes and should not be construed as investment advice. Investors should consult their own financial advisers before making any investments. The author is a CFA Charterholder with a vested interest in financial markets.

CFA Charter credentials - CFA Member Profile

CFA Badge

He blogs at:

https://ramakrishnavadlamudi.blogspot.com/

X (Twitter) @vrk100